One dog’s trick is another dog’s lifeskill

How we label, refer and view a process will have an effect on how we employ it. Words have powerful meanings that can be quite different depending on your culture, your background and your experience.

If we regard an activity as a hobby then we probably view the skills we learn for that hobby in a casual way. “Hobby” implies it is something we do for pleasure or when we are not working and we learn enough to satisfy the enjoyment in the hobby. What may begin innocently as a weekly class to learn about baking, pottery, or a new language may surprise us by filling all our free time, becoming an integrated social life and then graduate to a full time employment. Now the skills you are learning must also graduate to a whole new depth and competency.

You may be quite content to keep your hobby as a hobby and not want to learn more than is sufficient to meet the enjoyment of the activities and time invested. But only people, not dogs, have this notion that there is a difference between learning for a hobby and learning for work, the difference between “only” and hobby, and “proper” work. We were all drilled that work is not play. “Knuckle down”, “stop playing at it” …. many descriptions that keep work and play as strictly separated activities.

Dog training, teaching your dog or the activities you enjoy together also roll along the same scale. At one end a weekly evening class that fulfils the social needs of you and your dog with a dabble in training right through to teaching others, or training dogs as a professional and getting paid for it. Many of us started at one end and progress to the other, maybe not intentionally, but that is where the current takes us.

The dog has no concept that doing something for a hobby, or for fun, is any different than doing something as work, but we still bring the Victorian view that the dog should be “working, not playing”, we use the term to describe a dog that has a “good work ethic” and other such boll**ks

When I began an evening class over 40 years ago with my Cavalier, I did not know that it would become my third career and pave the way for travelling around the world. That long ago there was no “earning a living from dogs”, at best I could be employed as a kennel maid, and I was of the wrong gender to even be considered as a trainer of Guide Dogs. Training your dog was only a hobby and all you taught was obedience. There was no less passion about our dogs, but science had yet to reach the field and learning was passed down from teacher to pupil. I remember getting seriously excited about having three books on dogs!

Alongside the view that pleasure was not an integral part of training there was a hierarchy of “proper” dogs, and “real” training being superior to “just pet dog class”. I am afraid to say that even those involved in the sports of the times, Obedience and Working Trials, including me, regarding pet dog training as not serious training.

Today, we should all regard pleasure and play as an integral part of training (that is still a sticky word from the past) and lifeskills as greater value than sports skills. Skills for living surely has more weight than skills for prizes?

But does it?

I know of far too many dogs participating in sports that have never learned a necessary amount of lifeskills. We cannot lay down a blanket of tests that suit every lifestyle. The country dog needs a different set of skills to the urban dog and each household needs to decide their personal hierarchy of skills, as does each sport participant. We are not trying to teach all dogs everything but our choices should include the necessary lifeskills.

Whether we are talking about jumping skills, mixing with excited children, alerting on substances or halting at a roadside all that we teach a dog should be taught with the same standard and not be separated into tricks, just for fun, and lifeskills as serious training or sports success for our egos. To the dog it is not distinguishable. They cannot know when to try their best and when it is just for fun, but they can pick up our intent.

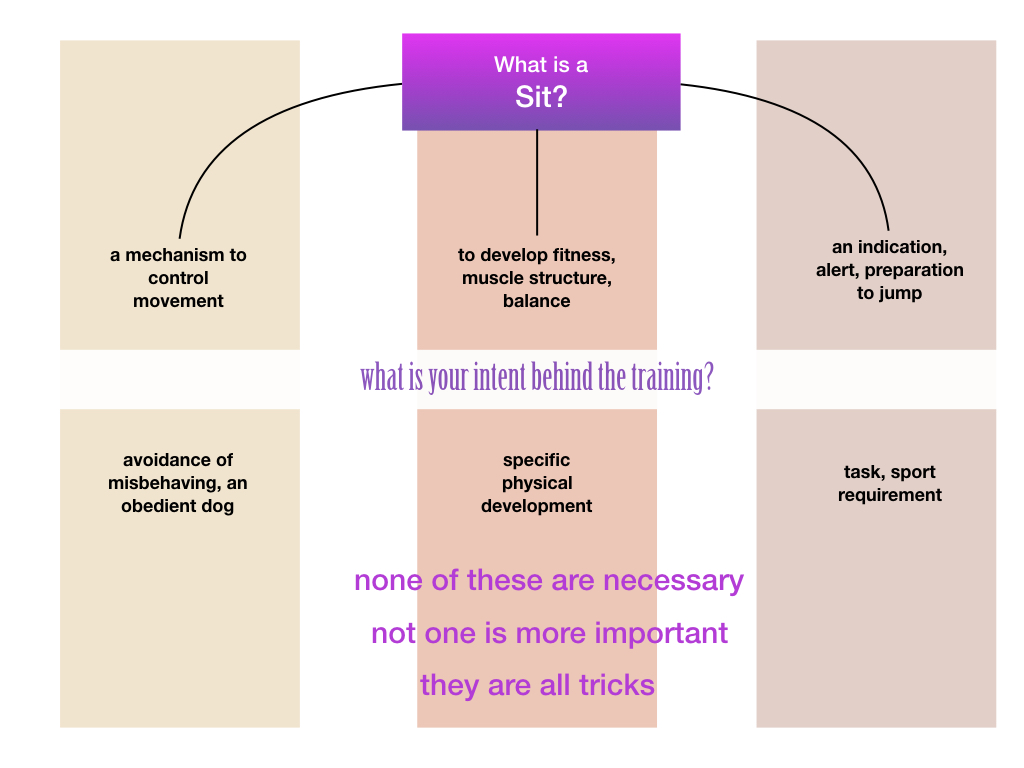

For as many dogs that have been taught to “park the butt for the nice person” there are as many reasons for doing it. Not the least of which “it is expected”, the historic view that an obedient dog equates to a well behaved dog which equates to a sitting dog. From the enthusiastic puppy owner training their first reliable response, to the fearful person requesting the dog in front of them sits as a avoidance of contact. Sit is taught as a trick, as a working skill for retrieving, as an indicating behaviour, as a pre-cursor to crossing a road, to have a leash clipped on, to make the dog wait at a door and 1000 more reasons.

Yes indeed, why does a dog sit? When does it benefit the dog, directly, not just to please people? To ponder, to think, to take a break?

We cannot teach something just for fun, it can never be just a trick, that is like saying you are going teach a child to cross a road, read a book, ride a bike for fun – it doesn’t have to be “done properly” because it is only a trick.

For all that we learn, we should learn it to the best of our abilities, that is the choice of the individual. “If you are going to do a job, do it well” But at the very least do it safely. By distinguishing jobs that need to be done properly, or well, from those that don’t we end up not learning honestly, we deceive ourselves.

This is about personal standards, you may need to choose to learn less but what you do learn is to your standard. When I went to glass blowing as a weekend hobby, I was taught only a few skills, but they were no less competent than someone on a three year course.

It is the same when teaching a dog. It is not different for serious trainers, or professionals it is about the person doing the teaching – their relationship with this individual dog, or person.

I have experienced learners with extremely high standards wanting to learn their training skills to a high degree. The surgeon with his Rhodesian Ridgeback teaching a chin rest. Taught with exceptional care, patience and precision. The decorator with the regard that this is just a hobby, of no importance and teaching their Labrador to beg, a trick. Taught so poorly the dog kept failing – and this became the entertainment and value to that person. The dog’s failure.

For everything we teach we make choices. Our first is surely “is this going to be safe and of benefit to the dog?” A direct benefit, not just because it benefits the dog by pleasing you. Your dog may be walking “nicely” on lead, but does this benefit the dog? You may say it prevents injury to their neck, but if their gait is such that is causes back pain, then it is not of benefit to the dog. If their anxiety levels are such to cause physiological stress, then it is not of benefit to the dog.

Our capacity to train many behaviours, (they are all behaviours), has exploded in the last 20 years and dogs have come along for the ride because they like their cookies and they like to please people. We have average folk with average dogs teaching impressive behaviours: Irish Terriers that learn to match different objects to specific containers, retrievers that can stack cups of matching colour, collies distinguishing a 1000 names of toys, demonstrate a concept of nouns and verbs, indicate on scat of rare species. These are no more tricks than is a sit, they are taught with diligence, care and consideration.

If your dog is going to learn from you, don’t diminish that learning by a variation of standards, or the next generation will have a new proverb to replace “calling wolf”. The moment you need your dog to respond, for their safety or your life, have they time to ask whether this is a trick or you really mean it?

Both are likely to end up on YouTube, but for different reasons.